Improving System Availability ― Part 1

Reliability, Maintainability, and Availability

This post is the first in a series to do with the use of risk management techniques to improve system reliability and availability in process and energy facilities.

Many organizations have mature safety programs, yet they continue to experience avoidable production losses, escalating maintenance costs, and declining asset performance. These outcomes are often addressed using the language and tools of safety risk management, even though the underlying problems are fundamentally different.

Formal risk management programs typically pursue two broad objectives. The first is to improve safety, protect the environment, and maintain a license to operate. The second objective is to enhance profitability by reducing downtime and improving asset utilization. Because both objectives are framed in terms of ‘risk reduction’, safety and reliability are frequently treated as variations of the same problem. It is therefore commonly assumed that improvements in safety will automatically improve reliability, and that reliability initiatives will inherently improve safety.

This assumption is misleading, and even counterproductive.

Safety and reliability belong to different classes of decision problems, governed by different constraints and measures of success. Understanding this distinction is essential if risk management is to be used effectively to improve system performance.

Safety Risk: Zero the Only Acceptable Target

Safety risk is asymmetric. A single catastrophic event can dominate all prior good performance. Ten years without an accident does not compensate for one catastrophic explosion, toxic release, or structural collapse. This means that safety risk management is not fundamentally an optimization problem because there is no optimum. Safety risk management is fundamentally a moral issue. (Further thoughts on this distinction are provided at the post AI and Process Safety Ethics: What’s a Human Life Worth?)

Risk can never be zero. Hazards always exist, those hazards have consequences (safety, environmental, financial), and they have a finite likelihood of occurrence. Therefore, safety can never be perfect.

Organizations may speak about ‘tolerable risk’, but this is a practical concession, not a philosophical one. From an ethical and regulatory standpoint, the goal of safety management is always further risk reduction, subject only to physical and societal constraints. There is no point at which a manager can say, ‘We are safe enough’.

This is why safety systems are frequently redundant, conservative, and expensive relative to their apparent utilization. Their value lies not in routine operation, but in preventing low-frequency, high-consequence events whose costs are effectively unbounded.

This way of thinking does not apply to reliability programs, for which there is indeed an optimum. Reliability belongs to a different class of decision problem — one governed by economics, system design choices, and diminishing returns.

Terminology

One of the problems to do with reliability management is that words are often used without being clearly defined. In particular, the word reliability is often used too loosely.

Definitions are needed for the words ‘reliability’, ‘maintainability’ and ‘availability’.

Reliability

Reliability applies to equipment items, or components within a system. It is defined as follows.

Reliability is the probability that an item will perform a required function without failure under stated conditions for a stated period of time.

This definition incorporates the following concepts:

Reliability has a probability value associated with it. This is a dimensionless number, unlike the term frequency.

The phrase required function refers to the fact that all items and systems are designed for particular tasks, or task sequences. For example, a water pump that is used to pump gasoline is not unreliable if it fails under the new conditions.

The stated conditions must be understood and met. For example, if an equipment item is operated outside its design temperature range, then its failure does not mean that it was unreliable.

Reliability covers only a stated period of time. Nothing can last forever, eventually everything wears out. (Sometimes the stated period of time refers to the number of cycles of operation for an item rather than its chronological age).

Maintainability

Maintainability refers to the effectiveness of the repair program. It can be defined as follows.

The maintainability of a failed component or system is the probability that it is return to its operable condition in a stated period of time under stated conditions, using prescribed procedures and resources.

Most reliability analyses assume that a repaired item is returned to service ‘as good as new’. This assumption is rarely true ― most items are restored to a condition that is somewhere between ‘as good as new’ and ‘failed’.

Availability

Availability is defined as follows.

The availability of a repairable system is the fraction of time that it is able to perform a required function under stated conditions.

Availability defines the degree with which a complete system, such as a compressor station, a refinery or an offshore platform, is able to perform as required.

When managers say that they want to improve reliability, they generally mean that they actually want to improve system availability.

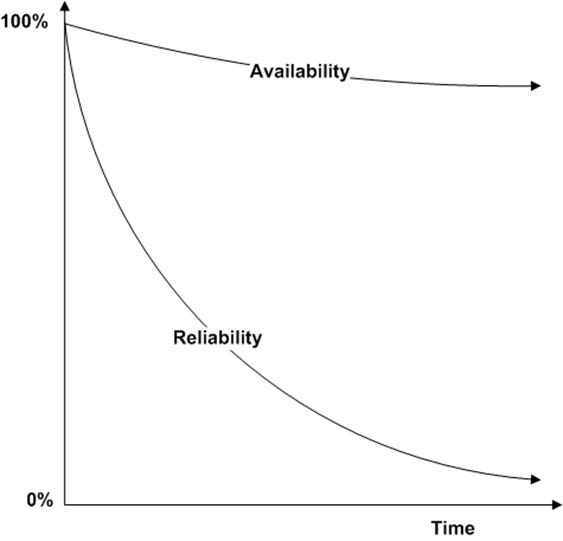

The difference between reliability and availability is illustrated in the sketch.

Over a long period of time availability levels out at (usually) quite a high number. This is because unreliable equipment items are either repaired or replaced. For example, the availability of a process unit may be say 95%, which means that it is operating 95% of the time. The reliability values for individual equipment items, however, trend asymptotically to zero. If an item is in service long enough, and if it is neither repaired nor replaced, it will eventually fail.

Conclusion

In many companies, process safety programs are mature. There is always room for improvement, but many managers are looking for opportunities to reduce operational and financial risk ― not just safety.

In this series of posts we describe how this may be done. In this first post, we stress the importance of defining terms.