Washington D.C. October 11, 2024.

The U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) announced today that it is launching an investigation into a fatal release of hydrogen sulfide at the Pemex petroleum refinery in Deer Park, Texas, which occurred yesterday, October 10. Two contract workers died as a result of the release, and an additional 13 workers reportedly were transported to local medical facilities.

Most readers of this blog will be familiar with the hazards of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Crude oil generally contains significant amounts of mercaptans, which break down to form H₂S. Therefore, H₂S is commonly found in oil refineries, pipelines and some chemical plants.

In spite of its familiarity, it is worth spending some time reviewing the properties of this dangerous gas and evaluating the ways in which we can respond to a leak.

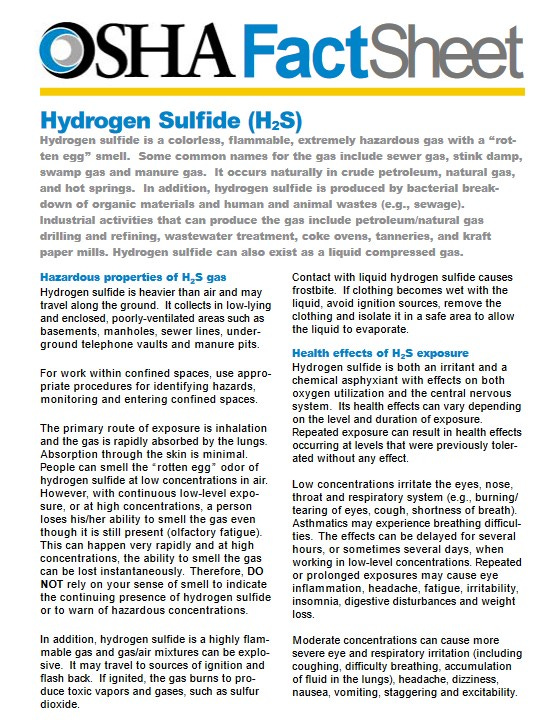

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has published a Fact Sheet for this widely used chemical. The Fact Sheet has two sections: one to do with the properties of H₂S, the other with how to respond to a leak of this commonly-found and dangerous gas. Let us work through some of the information in the first section of this document.

Hydrogen sulfide is a colorless, flammable, extremely hazardous gas with a “rotten egg” smell.

There is a degree of irony here. Given the prevalence of modern refrigeration, it is probably more appropriate to to state that rotten eggs smell like hydrogen sulfide.

It occurs naturally in crude petroleum, natural gas, and hot springs.

In petroleum/crude oil the sulfur is usually in the form of mercaptans: organic sulfur compounds with the formula R-SH, where R is an organic group.

Mercaptans break down naturally in storage tanks or pipelines under anaerobic conditions to create H₂S. In refineries the conversion is usually carried out in the Hydrotreating (Desulfurization) section. This process uses hydrogen gas and a metal catalyst (molybdenum or cobalt) to break sulfur bonds according to the following equation.

R-SH + H₂ → R-H + H₂S

The H₂S is then used to produce elemental sulfur and sulfuric acid, including the acid in your car battery. The point here is that H₂S is a reasonably valuable commercial commodity. It is not ‘just a nuisance’.

Hydrogen sulfide is heavier than air and may travel along the ground. It collects in low-lying and enclosed, poorly-ventilated areas such as basements, manholes, sewer lines, underground telephone vaults and manure pits.

Pedantically speaking, hydrogen sulfide is not heavier than air, it is more dense than air.

Models indicate that, at low concentrations, it will not necessarily ‘travel along the ground’. Therefore, it cannot be taken for granted that it is not present at the same elevation as the leak location.

. . . with continuous low-level exposure, or at high concentrations, a person loses his/her ability to smell the gas even though it is still present (olfactory fatigue). This can happen very rapidly and at high concentrations, the ability to smell the gas can be lost instantaneously.

Here is another ironical conundrum. ‘If you can smell H₂S then you are in danger. If you cannot smell H₂S you are in even greater danger’.

. . . hydrogen sulfide is a highly flammable gas and gas/air mixtures can be explosive. It may travel to sources of ignition and flash back. If ignited, the gas burns to produce toxic vapors and gases, such as sulfur dioxide.

The inability to detect H2S through the sense of smell does not prove that the gas is not present.

If sulfur compounds are present in furnace fuel, the on-going emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO₂) can create a health (as distinct from safety) hazard.

Repeated exposure can result in health effects occurring at levels that were previously tolerated without any effect.

We need to be concerned with both health and safety impacts of this gas.

The next section of the OSHA Fact Sheet discusses protection against H₂S exposure. We will review that section in a later post.