Acceptable Risk

One of the challenges that process safety professionals face is determining the level of acceptable risk. Risk can never be zero. If a facility operates for long enough, it is certain ― statistically speaking ― that there will be a serious accident. So how do we define what level of risk is acceptable? Working targets have to be provided, otherwise the facility personnel do not know what they are shooting for.

This is not a subject we can avoid ― after all, individuals and organizations are constantly gauging the level of risk that they face in their personal and work lives, and then acting on their assessment of that risk. Built into those assessments is an understanding of what levels of risk are acceptable.

Subjective Nature of Risk

Although it is necessary to determine the acceptable level of risk, the catch is that risk is fundamentally a subjective topic; it is not possible to dispassionately and objectively define what level of risk is acceptable and what is not. What is acceptable to one person may or may not be acceptable to another. The same goes for organizations ― some are more risk averse than others. Hence successful risk management involves understanding the opinions, emotions, hopes and fears of many people, including managers, workers and members of the public.

Factors that affect risk perception include the following:

Degree of control;

Familiarity with the hazard;

Direct benefit;

Personal impact;

Natural vs. man-made hazards;

Recency of events;

Effects of the consequence term; and

Comprehension time.

Regulatory Agencies

Regulatory agencies rarely provide absolute values for acceptable risk because, were they to do so, they would implicitly say that fatalities and injuries are acceptable. Any value that they propose would inevitably generate controversy.

Nor can a regulatory body, a professional society or the author of a blog such as this provide an objective value for risk. Each organization has to set its own targets.

Company Standards

In an industrial context managers make risk-based decisions regarding issues such as whether to shut down an equipment item for maintenance or to keep it running for another week. Other risk-based decisions made by managers are whether or not an operator needs additional training, whether to install an additional safety shower in a hazardous area, and whether a full Hazard and Operability Analysis (HAZOP) is needed to review a proposed change.

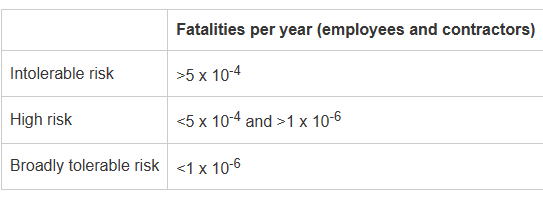

One company provided the criteria shown in the Table for its design personnel.

Their instructions were that risk must never be in the 'intolerable' range. High risk scenarios are ‘tolerable’, but every effort must be made to reduce the risk level, i.e., to the ‘broadly tolerable’ level.

Based on this Table, if a facility has 100 employees, then it is acceptable to have one fatality every 10,000 years. If there is a risk of having more than five fatalities every 200 years then the situation is deemed to be intolerable.

Many companies use a Table such as this to define levels of risk in the risk matrices that they use in hazard analyses.

Risk Matrices

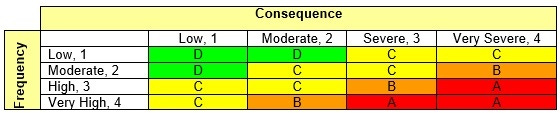

Risk matrices are often used during process hazards analyses. These matrices provide the team members with working levels of acceptable risk.

Typically each identified hazard is assigned a risk level on the following lines:

A (Red) Unacceptable. Immediate corrective action must be taken.

B (Orange). Risk must be reduced, but there is time to conduct more detailed analyses and investigations.

C (Yellow) Moderate. The risk is significant. However, cost considerations can be factored into the final action taken, as can normal scheduling constraints such as the availability of spare parts or the timing of facility turnarounds.

D (Green) Low. Requires action but is of low importance. In spite of their low risk ranking, ‘D’ level risks must be resolved and recommendations implemented according to a schedule; they cannot be ignored.

Once more, concerns to do with subjectivity have to be raised. How are the values assigned, and who sets the priorities?

Difficulties with Calculating Risk

The use of Tables such as the one just shown highlights a chronic difficulty with risk calculations, which is that the calculations themselves are subjective. For example, a manager may decide that certain employees need more training, but how does he or she assign a credible risk ranking to that decision? It’s a judgment call.

As Low as Reasonably Practical - ALARP

Some risk analysts use the term 'As Low as Reasonably Practical (ALARP)' for setting a value for acceptable risk. The basic idea is that risk should be reduced to a level that is as low as possible without requiring ‘excessive’ investment.

One panel has developed the following guidance for determining the meaning of the term As Low as Reasonably Practical.

Use of best available technology capable of being installed, operated and maintained in the work environment by the people prepared to work in that environment;

Use of the best operations and maintenance management systems relevant to safety;

Maintenance of the equipment and management systems to a high standard;

Exposure of employees to a low level of risk.

The catch with this approach is that it can lead to circular reasoning. How do we assign numerical values to words such as ‘excessive’, 'best available technology' and ‘reasonable’? Once more, this is a subjective evaluation.

Another difficulty with the use of ALARP is that the term is likely to be defined by those who will not be exposed to the risk, i.e., the managers, consultants and engineers who work safely in offices located a long way from the facility being analyzed. Were the workers at the site be allowed to define ALARP it is more than likely that they would come up with a much lower value.

Risk Boundaries

Another way of determining acceptable risk is to use risk boundaries, such as those shown in the chart, which is an F-N curve family. Between those boundaries, a balance between risk and benefit must be established. If a facility proposes to take a high level of risk, then the resulting benefit must be very high.

De Minimis Risk

The notion of de minimis risk is similar to that of ALARP. A risk threshold is deemed to exist for all activities. Any activity whose risk falls below that ‘low’ threshold value can be ignored ― no action needs to be taken to reduce the risk. Once more, however, an inherent circularity becomes apparent: for a risk to be de minimis it must be 'low', but no prescriptive guidance as to the meaning of the word 'low' is provided.

Citations / Case Law

Citations from regulatory agencies provide some measure for acceptable risk. For example, if an agency fines a company $50,000 following a fatal accident, then it could be argued that the agency has set $50,000 as being the value of a human life. (The agency's authority over what level of fines to set is, however, constrained by many legal, political and precedent boundaries that are outside their control, so the above line of reasoning provides only limited guidance at best.)

Even if the magnitude of the penalties is ignored, an agency's investigative and citation record serve to show which issues are of the greatest concern to it and to the community at large.

Indexing Methods

Some companies and industries use indexing methods to evaluate acceptable risk. A facility receives positive and negative scores for design, environmental and operating factors. For example, a pipeline would receive positive points if it was in a remote location or if the fluid inside the pipe was not toxic or flammable. Negative points are assigned if the pipeline was corroded or if the operators had not had sufficient training. The overall score is then compared to a target value (the acceptable risk level) in order to determine whether the operation, in its current mode, is safe or not.

Although indexing systems are useful, particularly for comparing alternatives, it has to be recognized that, as with ALARP, a fundamental circularity exists. Not only has an arbitrary value for the target value to be assigned, but the ranking system itself is built on judgment and experience, therefore it is basically subjective.

Conclusion

Based on the above discussion, it may be concluded that attempts to determine levels of acceptable risk are not all that helpful. There are so many uncertainties, and there is so much subjectivity, that such calculations are not likely to be beneficial.

However, assessments of acceptable risk can lead to useful comparisons between two or more options. The focus is on relative risk, not on trying to determine absolute values for risk and for threshold values.

very Valuable